I am likely going to be blogging quite a bit about Palestine and Israel over the next few months as I do extended in-country research. My arrival was

either timely or horrendously timed – I’m still not sure which – as my intended

research project has been stymied amidst violence. Since 1 October, 25

Palestinians and 4 Israelis have been killed - including a 13 year old

Palestinian who was shot in the neck yesterday while protesting outside

Ramallah, where I’m currently staying.

Before I discuss the conflict and the current round of violence, I want

to contextualize the conflict for our friends and readers in the US. This context is particularly important for

Americans to understand as US Presidential candidates will continue to discuss

Israel and Palestine before the next election. One cannot engage fully on the

topic of Israel and Palestine – one cannot hope or push for peace – without

understanding the context of the occupation of Palestine.

I’m using the word ‘occupation’ in a legal sense, meaning that

Palestinian life and territory is, for the most part, placed under the

authority of Israel’s military, and by extension the Israeli government. The

fact that Israel is an occupying power is not really open for legal dispute as

findings from both the International Court of

Justice and the Israeli

Supreme Court have concluded that Israel is the occupying power, as have

the world’s leading experts on the issue (see the analysis of Yoram Dinstein,

the former rector of Tel Aviv University, at pages

20-23 here).

Today, I’m only able to discuss the West Bank, exclusive of Jerusalem,

as that alone requires a two-part post. Throughout this week, though, I’ll be

posting on Palestine and Israel, and on the context of the conflict.

The Year-Based Borders

The borders between Israel and Palestine have been massively disputed,

leading to serious problems. There are

two internationally discussed borders: ‘48 and ‘67. Because people chose to colloquially name these

borders after years in which conflicts began, it can be a bit confusing.

The 1948 borders are based on the UN’s plan of partition

and the creation of two states, Israel and Palestine. For reasons stemming from colonialism, no one consulted the Palestinians, so the plan was

just imposed on them.

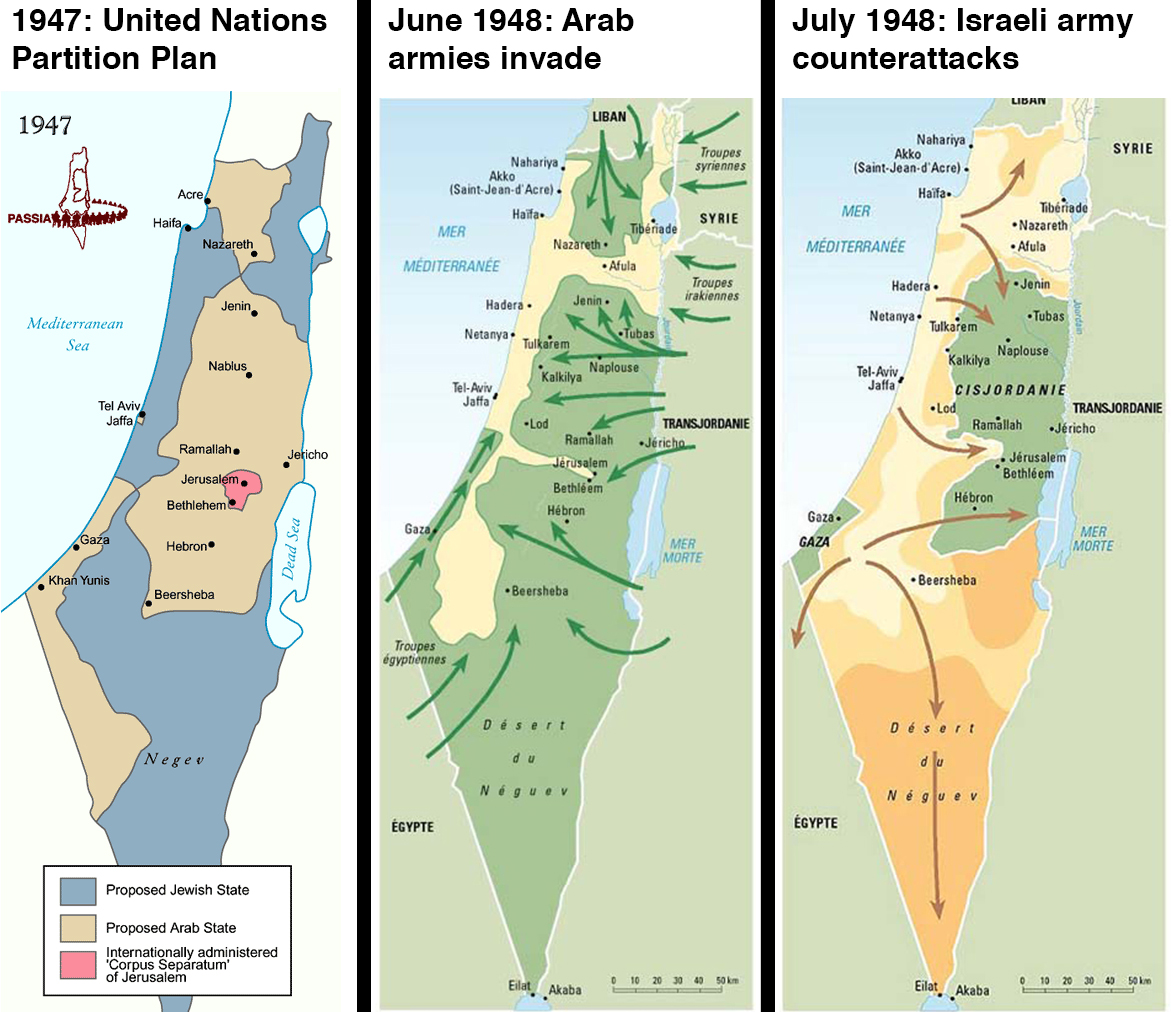

In the map below, the ’48 borders are the left-most picture.

In 1948 and 1949, the Arab-Israeli war led Israel to take over significant land portions. In the map below, you can see the ‘1949 armistice’ borders, which are also known as the ’67 borders, referring to the borders before the Six Day War in 1967.

During the 1967 Six Days War, for reasons still steeped in colonialism,

Israel wasn’t fighting Palestine. It was

fighting Egypt for the Gaza Strip and Jordan for the West Bank and Jerusalem.

Egypt and Jordan were in turn supported by Syria, Iraq, and Palestinian

groups.

Israel initiated

the war on 5 June, after a military build-up indicated a likely

conflict. With a preemptive air assault,

Israel destroyed 90% of Egypt’s air force while it sat on tarmacs. The Arab

militaries consolidated leadership, but Israel was able to capture Palestinian

territories by 7 June, when the UN Security Council called for a cease-fire. It took until 10 June for Syria to accept the

cease-fire. On 9 June, it lost control

of the Golan Heights.

During the war, Israel captured Jerusalem, the

West Bank and the Gaza Strip, but has gradually given back parts of this to

Jordan and Egypt, in exchange for peace agreements. Under the 1993 Oslo

Accords, Israel was supposed to eventually withdraw to the ’67 borders, giving

Palestine control over its territory.

Yasser Arafat, Yitzhak Rabin, and Shimon Perez won the Nobel Peace Prize

for this plan, and members of the international community still expect Israel

and Palestine to use the ’67 borders as the starting point for any permanent

solution, but Israel considers these borders “indefensible.”

Understanding the West Bank’s

Area Divisions

Under the 1993

Oslo Accords, between Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organization,

the West Bank of Palestine is divided into three areas – A, B, and C. The divisions are mapped out in the right-hand map.

On the right-hand map, Area A is the dark green.

On the right-hand map, Area A is the dark green.

Area A is placed under the control of the Palestinian Authority, though it’s important to know that Israeli forces still operate in Area A. This became very obvious this week when Israeli Defense Forces demolished homes (or marked them for demolition) in al-Bireh and Ramallah, both communities in Area A.

Portions of Area A are, as I’m often told, a little bubble of normalcy in an

inherently unusual situation.

Construction, which is not dependent on Israel’s approval, has led to

some really nice buildings, as well as some pretty out-there ones, like this

building, which houses the Palestinian Red Crescent Society (their equivalent

of the American Red Cross).

While the eight largest Palestinian cities – Nablus, Jenin, Tulkarem,

Qalqilya, Ramallah, Bethlehem, Jericho and 80% of Hebron – are in Area A, the

area represents approximately 18% of the West Bank (page

3 here).

It's worth noting that while the 80% of Hebron is considered part of Area A, locally it's divided into H1, controlled by the Palestinians, and H2, controlled by the Israelis.

It's worth noting that while the 80% of Hebron is considered part of Area A, locally it's divided into H1, controlled by the Palestinians, and H2, controlled by the Israelis.

The Palestinian Authority in the West Bank is currently controlled by

the Fatah party, which is responsible for passing Palestine’s laws and is the

internationally recognized government of the State of Palestine. Fatah’s rule

is disputed, though, as Hamas won the last national elections. Despite the elections being democratic, free, fair, and transparent, Hamas has been

unable to govern due to international pressure, which refused to recognize Hamas. Israel arrested members of Hamas's political apparatus, and the international community chose to continue to recognize Fatah as the ruling government (I’ll discuss that

more on Wednesday, when I’ll discuss the situation in Gaza). Politically, the country can’t have new

national elections – ones that would address both the West Bank and Gaza –

until the dispute between Hamas and Fatah is resolved.

On the other hand, Area C was placed under the exclusive control of

Israel, meaning Israel decides what portions of Area C Palestinians can

use, how things like water and electricity can be developed, whether buildings

can be upgraded, etc.

In the right-most map again, Area C is everything that’s not green:

In the right-most map again, Area C is everything that’s not green:

Area C represents approximately 61% of the territory in Palestine, and

almost all of Palestine’s agricultural and natural resources are located in

this area.

Area C represents approximately 61% of the territory in Palestine, and

almost all of Palestine’s agricultural and natural resources are located in

this area.

Palestinians can access about 1% of Area C (see page

ix here).

But, Israel is able to access the totality of Area C, and this is where

Israel has constructed many of the “settlements,” housing groups that are

unlawful under international law, most notably the

Fourth Geneva Convention.

The Fourth Geneva Conventions prohibit the forcible

transfer of civilians into occupied territory. Some note (as Dinstein does

at page 241) that Israel doesn’t always force the transfers – meaning it

doesn’t require Israelis move into the territory. The International Court of Justice addressed

this in the Palestinian Wall advisory

opinion, stating that the Geneva Conventions prohibition attaches not just

those transfers where the state requires a citizen to move, but also to “any

measures taken by an occupying Power in order to organize or encourage

transfers of parts of its own population into the occupied territory.” (at

1042).

The only Israeli settlements within the West Bank that can be

defensible under international law are, as Dinstein points out, those where the

individual acts on their own accord to establish a community on land previously

held by individuals from which they acquired lawful title (Dinstein at 241).

Even then, precedence

from World War II suggests that sometimes a property transfer can be

considered forced simply because of the legal, political and social conditions

surrounding the transfer made it necessary, even if it wasn’t absolutely or

strictly required by law. This standard was used to return property transferred

during Nazi-era Germany.

The settlements supposedly take up approximately 1% of the land in the West Bank, but their

build-up – the things around them that are used to serve the settlements,

including security, take up

approximately 42% of the West Bank’s land (and that’s, apparently, based on legal interpretations that are generous

to Israel). And while the State of

Israel claims that settlements only operate on “state” owned territory (which

is indefensible as noted above), it appears that at

least 21% of the built-up areas are on private Palestinian land.

The settlements are even more problematic when they engage in “pillage,”

or the taking of materials and resources from the occupied territory for the

benefit of the private individuals. Pillage is a war crime and is prohibited in

all instances. There can literally be no justification for it.

And yet, every time an Israeli settlement or a company takes minerals

or other resources from the territory, it is engaging in pillage.

The World Bank estimates that Israeli control over Area C costs the

Palestinian economy $3.4 billion

dollars, or roughly 35% of the Palestinian GDP (page

x, para ix, of this link). Much of

that money is transferred through the settlements into Israel’s economy, but

some of it is simply lost because of lost opportunities due to Israeli

restriction on Palestinian use.

Area B has approximately

21% of Palestinian territory. Problematically, Area B is pretty much a “no

man’s land.” Area B connects the cities

in Area A – the ones under Palestinian control – and is supposed to be governed

by Palestine and Palestinian law. But, Palestinian security forces can’t really

operate there, and while Israeli forces do, they often don’t enforce the

law. So, Area B is impoverished, under

developed, and often (I’ve been told) lawless.

Area B is the light green in the right-most map:

Then Israel Built a Wall…

In 2002, Israel built a wall to “protect its borders” and “keep

terrorists out." Yes, sometimes the Israeli government sounds like Donald Trump

– they even built doors

in the wall, called checkpoints. It's a bit unfair to compare Israel to Donald Trump here. His suggestion comes from a lack of real foreign policy knowledge. In 2002, Israel was in the midst of the Second Intifada, a battle with Israel that ultimately led to Yasser Arafat's death.

The Second Intifada started when Ariel Sharon, a former commander in the Israeli army, who many hold responsible for a massacre at the Sabra refugee camp, marched on Islam's holiest site in Jerusalem (the third holiest in Islam), and declared the site would remain under Israeli control.

While the area is also considered a sacred area for the Jewish faith, Israeli law prohibits Jewish adherents from going to the area, and the Al Aqsa Compound remains under Jordanian guardianship (another remnant of colonialism) and has long been protected for Muslim followers.

Under the terms of Oslo, East Jerusalem is still to be decided, but the intention of the international community has always been that East Jerusalem would return to Palestinian control. By asserting that Al Aqsa would remain under perpetual Israeli control, Sharon was asserting that Israel would continue to control East Jerusalem, denying Palestine the capital it has long wanted.

Palestinians were outraged, and began protesting. The protests grew and led into a 5 year conflict.

The Second Intifada was brutal on both sides, though Palestinian civilians suffered the most. Approximately 3,000 Palestinians were killed and 1,000 Israelis. This Intifada lasted from 2000-2005, and during that time Sharon - who had a limited political career immediately before his infamous march - ran and was elected Prime Minister of Israel. His government announced the construction of the Annexation Wall as a means of securing Israel's "borders".

The problem is that the wall doesn’t actually follow Israel’s internationally recognized borders. As the UN explains, “the vast majority of the [wall] route is located within the West Bank,” meaning within Palestinian territory.

The wall also effectively usurps East Jerusalem, despite the commitment within the Oslo Accords to revisit the question of Jerusalem.

The Second Intifada started when Ariel Sharon, a former commander in the Israeli army, who many hold responsible for a massacre at the Sabra refugee camp, marched on Islam's holiest site in Jerusalem (the third holiest in Islam), and declared the site would remain under Israeli control.

While the area is also considered a sacred area for the Jewish faith, Israeli law prohibits Jewish adherents from going to the area, and the Al Aqsa Compound remains under Jordanian guardianship (another remnant of colonialism) and has long been protected for Muslim followers.

Under the terms of Oslo, East Jerusalem is still to be decided, but the intention of the international community has always been that East Jerusalem would return to Palestinian control. By asserting that Al Aqsa would remain under perpetual Israeli control, Sharon was asserting that Israel would continue to control East Jerusalem, denying Palestine the capital it has long wanted.

Palestinians were outraged, and began protesting. The protests grew and led into a 5 year conflict.

The Second Intifada was brutal on both sides, though Palestinian civilians suffered the most. Approximately 3,000 Palestinians were killed and 1,000 Israelis. This Intifada lasted from 2000-2005, and during that time Sharon - who had a limited political career immediately before his infamous march - ran and was elected Prime Minister of Israel. His government announced the construction of the Annexation Wall as a means of securing Israel's "borders".

The problem is that the wall doesn’t actually follow Israel’s internationally recognized borders. As the UN explains, “the vast majority of the [wall] route is located within the West Bank,” meaning within Palestinian territory.

The wall also effectively usurps East Jerusalem, despite the commitment within the Oslo Accords to revisit the question of Jerusalem.

Individuals living in areas between the internationally recognized

borders and the Wall

require permits to continue living in their homes, regardless of how many

generations they’ve owned that land. This affects approximately 11,000

people in 32 communities. Another 150 communities have

land that is located behind the Wall, so they cannot access the land without

special permits or prior arrangements with the Israeli government.

In the next post, which will come tomorrow, I’m

going to divvy up my home state of Ohio to reflect the reality of what this

means in Palestine. The numbers are

difficult to understand – and it becomes hard to contextualize if you’re not

familiar with the territory. So, I’m

taking Ohio as that’s where the majority of my friends and family are from, and

it’s a relatively easy place for most Americans to understand.

No comments:

Post a Comment